Covering your points in enough detail to demonstrate your knowledge.Just remember that in order to teach, we first have to show that we are worthy of our audience’s attention. However, in planning informative speeches, we can get so wrapped up in the topic that is easy to forget about the elements of credibility. It seems to be common sense that we do not listen to speakers who do not know what they are talking about, who cannot relate to us, or who give the impression of being dishonest. To avoid this pitfall, there are at least three ways to boost your credibility as a speaker by establishing your expertise, helping your audience identify with you, and showing you are telling the truth (see examples in Table 15.1).

In addition, they look at and listen to the speaker to determine if s/he is a reliable source of information.Īudience members have no motivation to listen to a speaker they perceive as lacking authority or credibility-except maybe to mock the speaker.

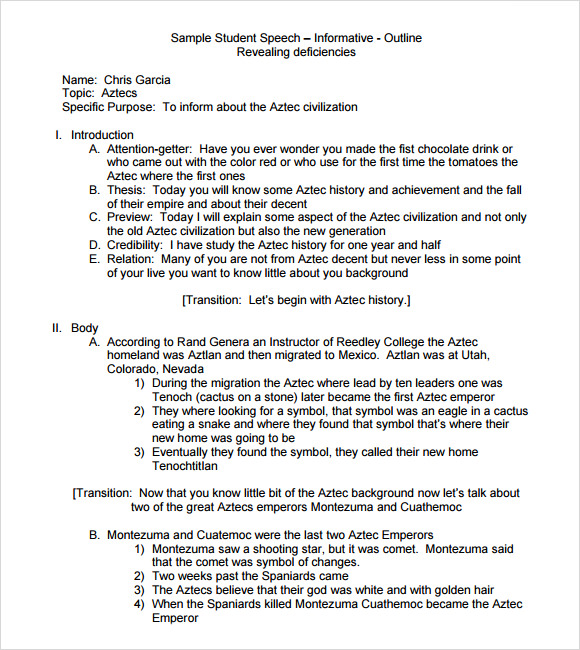

In many cases, the audience has no prior knowledge of the speaker, so they make judgments about the quality of the evidence and arguments in the speech. Peterson, Stephan, and White (1992) explain that there are two kinds of credibility the reputation that precedes you before you give your speech (antecedent credibility) and the credibility you develop during the course of your speech (consequent credibility). Credibility, or ethos, refers to an audience’s perception that the speaker is well prepared and qualified to speak on a topic (Fraleigh & Tuman, 2011). Informative Speakers are CredibleĪn objective approach also enhances a speaker’s credibility. When writing your speech, present all sides of the story and try to remove all unrelated facts, personal opinions, and emotions (Westerfield, 2002). You are teaching them something and allowing them to decide for themselves what to do with the information. You are not asking your audience to take action or convincing them to change their mind.

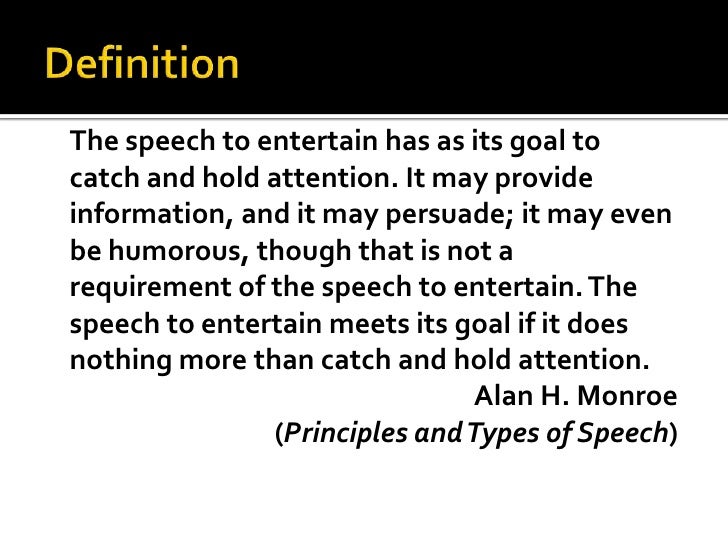

Can you imagine how speeches on witchcraft, stem cell research, the federal deficit, or hybrid cars could be written either to inform or persuade? Informative speeches need to be as objective, fair, and unbiased as possible. For instance, in a speech about urban legends (Craughwell, 2000), your specific purpose statement may be: “ At the end of my speech, my audience will understand what an urban legend is, how urban legends are spread, and common variations of urban legends.” The topic you choose is not as important as your approach to the material in determining whether your speech is informative or persuasive (Peterson, Stephan, & White, 1992). In spite of this caveat, when planning your informative speech your primary intent will be to increase listeners’ knowledge in an impartial way. Second, a well-written speech can make even the most dry, technical information entertaining through engaging illustrations, colorful language, unusual facts, and powerful visuals. First, all informative speeches have a persuasive component by virtue of the fact that the speaker tries to convince the audience that the facts presented are accurate (Harlan, 1993). Even in situations when the occasion calls for an informative speech (one which enhances understanding), often persuasive and entertaining elements are present. Although these general purposes are theoretically distinct, in practice, they tend to overlap. Most public speaking texts discuss three general purposes for speeches: to inform, to persuade, and to entertain. Now that you understand the importance of informing others, this next section will show you the speakers’ responsibilities for preparing and presenting informative speeches.

Human history becomes more and more a race between education and catastrophe.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)